Boosters and Doomsters

The real divide in British economics

The most important divide today in British economic policy is between people who think that the UK's dire economic position is largely a failure of domestic policy, and people who think it is mainly due to factors outside the country's control, or at least its medium-run ability to fix. Let’s call them Boosters and Doomsters.

Boosters say that with better economic policy, we could get a lot richer, pretty quickly. They point to how much of the UK economy is obviously broken. Housing supply is both clearly severely constrained – the cost of purchasing a house in many parts of the country is 5-10 times the cost of building it – and clearly the root cause of high housing costs. If you subscribe to the "housing theory of everything", then this by itself may create a lot of other problems, like people being unable to move for more productive jobs and labour markets being underdeveloped because workers aren't able to move there. Andrea can’t afford to move to Cambridge to get a higher paid job, which makes her produce less, and her would-be employees end up producing and innovating less because they don’t get to work alongside her.

Lots else is wrong with the British economy in ways that policy seems able to fix, at least in principle. The UK’s corporate tax is one of the most badly structured in the world, ranking 35th out of 36 countries in the OECD in terms of how heavily we tax capital investments made by businesses. There are many other extremely important areas that the UK does pretty badly on – infrastructure, healthcare, policing, regulation, access to capital, immigration and education are all pretty dysfunctional and affect big parts of the economy.

They might also point to the fact that the UK is a lot poorer than many other developed countries. There is a common tendency among Brits to believe that we are as rich as everyone else and think that if US GDP per capita is higher than ours, it's offset in terms of actual living standards by the worse crime, higher health costs and spending, higher levels of inequality, and shorter holidays that Americans have to put up with. But even if we grant that argument (which I think is a cope, but anyway), it still doesn't explain why we're poorer than Canada, Australia, Germany, South Korea (which has rapidly overtaken us over the past decade), and so on. Even France is richer than we are.

Fundamentally, Boosters think growth is really, really important, because it’s the only thing that allows us to overcome zero-sum problems and reduce human misery overall. We don’t have to worry today about children working in mines or people starving in the streets because we have so much money that we can easily provide for them – thanks to growth. And if growth compounds, then small increases today can mean huge gains for our children, grandchildren and older selves. And they’re often frustrated at other people for treating it as a second-tier priority, when in their view it unlocks solutions to almost every other problem we have – and the downside of trying and failing is nothing compared to the upside of succeeding.

These Boosters are people like Anton Howes, Matthew Clifford, Shreya Nanda, Stian Westlake, Aaron Bastani, Aria Babu, Tom Forth, and Tom Westgarth and Andrew Bennett. Note that this cuts across standard left/right divides. Even if these people disagree about how to improve things, their fundamental view is that the UK could be much, much richer if we improved policy.

The second group is much more pessimistic. Let's call them the Doomsters. In their view, the country faces enormous problems that mean we're stuck on low growth for the foreseeable future, unless we happen to get very lucky on things outside of their control. This group highlights that governing involves trade-offs, that policy design is difficult, and that there are no free lunches – for example, many Doomsters believe that the UK could improve growth by improving skills, but that this would require huge amounts of government spending and bear fruit over several decades. They can, I sense, be frustrated at what they see as the freewheeling dilettantism of many boosters who think they have one weird trick to double the UK’s economic growth rate.

I believe a significant influence on this group is the work of Dietrich Vollrath, who argues that the slowdown in global economic growth in recent decades is not that technology is advancing less rapidly (a theory I explored for the BBC recently), but largely shifting demographics caused by an ageing society. I'm simplifying here, but Matt Clancy's review was good. But Vollrath was writing specifically about the US – and less applicable, perhaps, to a country with a GDP per capita that is 32% below America’s.

In this story, the UK is basically locked in to slower growth, because we have fewer young workers and more old people. This creates a bit of a death spiral. Fewer workers means fewer people to act as entrepreneurs and innovators, and also fewer taxpayers to fund the higher spending needed for the extra and longer-lived old people. This means that per capita taxes may have to rise on those who are left working, which slows down growth as well. Even if we could eventually raise the birth rate to counteract this – and the evidence is depressingly thin that government policy can meaningfully encourage people to have more kids – that won't show benefits for decades.

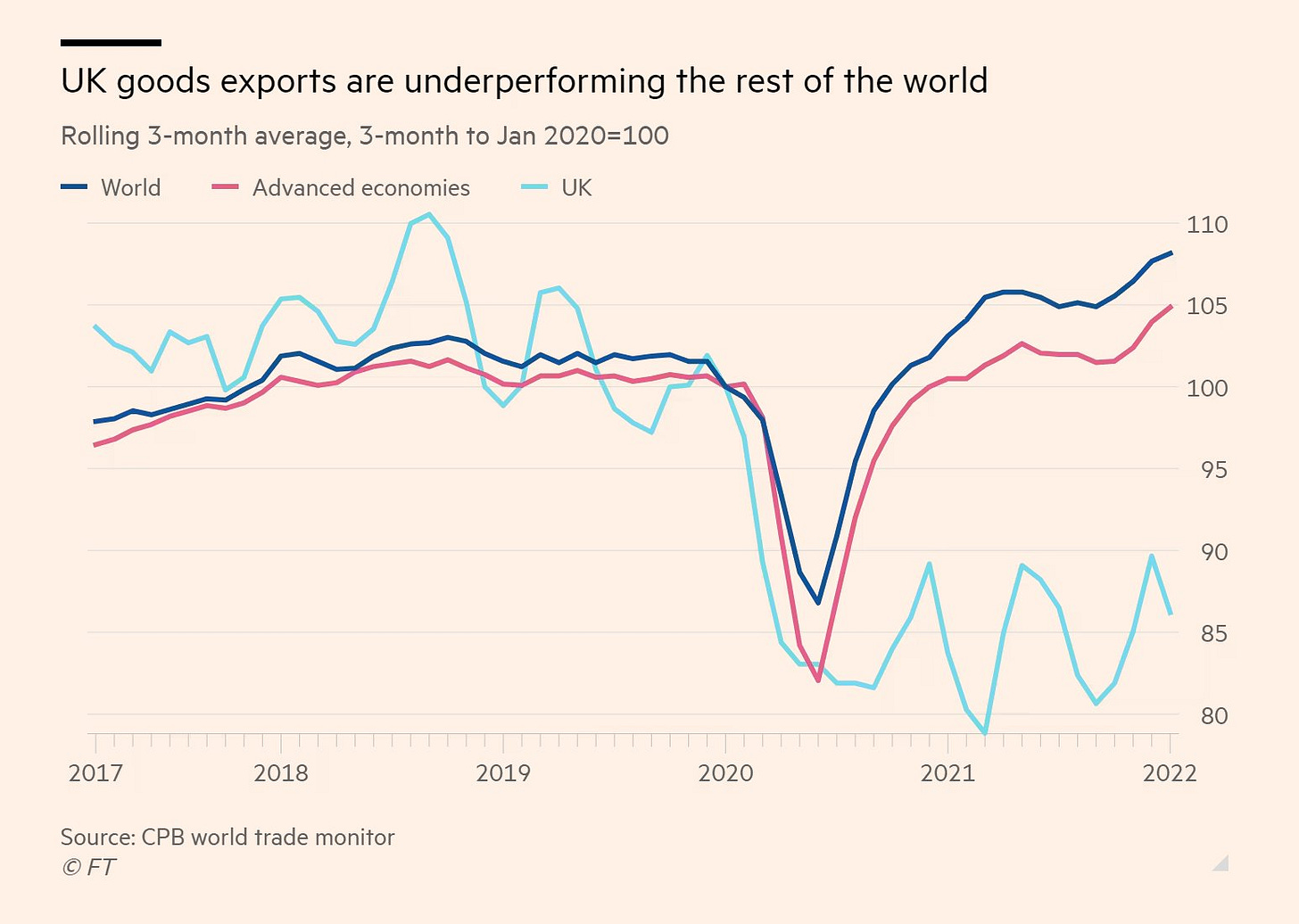

Doomsters also argue that, even if there are gains that might come from better policy, they probably aren't very large (with perhaps one or two exceptions). Giles Wilkes is one of the most challenging and interesting of the Doomsters, and argues that you can't just "unleash growth", because the gains from any realistic public policy reform we could imagine would still be tiny compared to overall GDP. Doomsters also often make this argument about housing supply – even if more housing would be a good thing, they think it's not feasible to build that many more that it would really change much. I think the one policy choice that the Doomsters do think made a big difference was Brexit, which is certainly within our power to reverse in principle, but practically isn't really because of the politics of it. On this point I entirely agree – it was a bad decision that is already visibly making us poorer, with very limited benefits.

Doomsters might also point to the UK's exposure to global economic trends and suggest that a lot of our fortunes are not really in our control, at least in the short run. There's not really very much we can do to deal with a massive rise in energy costs caused by the war in Ukraine, at least in the short run, and the things we can do will take years and cost a lot of money, which means higher taxes and, yes, lower growth. As well as Giles Wilkes, I would suggest that Tim Pitt, Torsten Bell and Rupert Harrison* appear to me to be in this group – all are smart, informed, and have more experience inside government than the majority of the Boosters. (Apologies if any think I’ve mischaracterised them in any way.)

Obviously there are Boosters who worry about the things Doomsters worry about, and Doomsters who want to do some of the things Boosters favour because they can hardly hurt. But often the divide leads to stark differences over, for example, whether the best way of analysing a new budget or policy change is how it affects the distribution of income or how it affects economic growth. Or, as we see in the Tory leadership election, whether it’s a bad idea to raise corporation tax for growth reasons, or if it won’t really do much to growth anyway so reducing the deficit should be the priority.

Institutionally, the Doomster view seems very powerful at the Treasury, and the absence of a more optimistically Boosterish department may be behind some calls to break it up. I don’t really know what either of the candidates for Tory Party leader really believe on the most important issues, so I’m not going to speculate about them. If Janan Ganesh is right that the vibes of “know-it-all” Sunak vs “no-nonsense” Truss will decide which of them makes it to No 10, I think it will be the Booster / Doomster divide among the people they listen to that decides what they actually do there.

* I think I miscategorised Rupert here - sorry!

Elsewhere…

I helped to bring out Works in Progress’s eighth issue, with great articles by Stewart Brand on sailing and maintenance, Saloni Dattani on fixing peer review, and many more, plus a wonderful documentary about a DIY internet in Cuba.

And I reviewed Nicolas Petit’s Big Tech and the Digital Economy: The Moligopoly Scenario for the History of Economic Ideas journal.

And, by popular demand, I’ll be releasing a new issue of my “Things I Recommend You Buy” post soon. To get it, don’t forget to smash that subscribe button.